(left to right) Kristie Lu Stout (CNN), Rakesh Kacker (TRAI India), Eddie Cheung (HKSAR), and Amelia Day, ‘Regulating A Real World’, 26 October 2005

ASEAN DIRECTIVES FOR A BETTER BROADCASTING ENVIRONMENT

Accelerating ASEAN 2020

“One Vision, One Identity, One Community”

by Amelia Day

DISCLAIMER STATEMENT: Information presented on this writing is compiled from many sources and therefore considered public-domain information (unless otherwise noted) and may be distributed or copied. Use of appropriate byline/photo/image credit is requested. While we make every effort to provide accurate and complete information, various data such as names, dates, etc. may change prior to updating. We welcome suggestions on how to improve these thus correct errors. Some of notification on this writing may contain references (or pointers) to information created and maintained by other organisations.

ASEAN DIRECTIVES FOR A BETTER BROADCASTING ENVIRONMENT

Accelerating ASEAN 2020 “One Vision, One Identity, One Community”

Abstracts

This paper first studies how broadcasting dispensing socio-cultural values, thus far studies the enclosed concept to assert economy incursion into a society. Knowing how this ethereal mechanism works, together with the knowledge of broadcasting industry structure, we will weigh up the mechanism to promote ASEAN region, hence ASEAN’s Vision 2020. To accelerate the Vision, we propose a concept of ASEAN Directives for a better broadcasting environment.

ASEAN as institution is evolving, forming an integrated economy community with legally-binding ASEAN Charter 2020. Due to the positive process in ASEAN, proposing the Directives of Broadcasting would mean accelerating the concept of integrated ASEAN Economic Community. On the other way round, legally binding ASEAN Directives on broadcasting to regulate the industry would form a resolution for a better broadcasting environment in the region.

Looking into the chaotic structure of broadcasting industry in each ASEAN member country, this writing suggests a comprehensive background and compartmentalization thus corresponding solutions for regulating the industry in the region. ASEAN Directives, subsequently, would show the way to Vision 2020 of the legally binding ASEAN Charter.

ASEAN DIRECTIVES FOR A BETTER BROADCASTING ENVIRONMENT

Accelerating ASEAN 2020 “One Vision, One Identity, One Community”

Before questioning the concept of ASEAN Directives, let’s examine how the broadcasting signal is transmitting values, and what the ethereal mechanism does really do or say. Appreciating MTV Asia signals as means of economy packet could broaden our perspectives of the Directives.

A. SOCIO-CULTURAL [AND ECONOMICS] VALUES OF BROADCASTING

Broadcasting signal is transmitted and received at the same time and same place. Of any distribution channel (satellite, cable or terrestrial) broadcasting signal is not just a technical issue. Broadcasting transmission has values that are beamed along: a three-fold-dimension message of ideology, socio-cultural and political. However, there are no so-called neutral values. By beaming the signal, someone has intentional impacts of values to aim at the end of the day.

“Social science research in [T]elevision [S]tudies considers how television has a role in reproducing the pattern of values and the divisions between groups and classes of people in the society, in other words how television represents and affects the social order … [B]y investigating these aspects of television, it can be seen how television gives different kinds of value and legitimacy to different facets of social life, and separates out or unifies people with each other.”[i]

The messages are conceptualised and produced in formats of entertainment, information or education. Not just there, these messages are sent and resent as many times as the television station is concerned. The repetition will crystallize towards passive audience. The crystallization will formulate new ideology and values for them.

Take an example of teenagers today in Indonesia. He or she doesn’t know the real meaning of “Gue banget!” The translation of this phrase would go as far as an emphasis of “my self”. For a teenager-at his or her age of searching for self-being a “my self” is about being comfortable with a concept of living. When teen audience is shown what is shown crudely on television, and feels good about it, then the captured images and lifestyle is becoming “reality at will”[ii]. Since television has its own world to tell, instantly what matters to audience is the performance: what is shown audio visually[iii].

MTV logo is copyrighted, and hip hop picture is quoted from about.com

MTV logo is copyrighted, and hip hop picture is quoted from about.com

This kind of “gue banget” reality is the product that MTV has been selling for the last decade. Music, on the other hand, is just a side-product. Capitalism aims at teenager is well-thought of by media industrialist such as MTV. Teens are shown how to become individualistic in mind and behaviour. Teen-target capitalism is a social system based on the principle of individual rights of a certain age group. The term capitalism is used here in a broader philosophical political sense; and not in narrower economic sense, i.e. a free-market.[iv] As the object of capitalism, teenagers in Indonesia speak the same language, dance the same move, and dress up the same way with what is shown on television; or with other teenagers in the region where MTV Asia signals are directed.

Vividly, teenagers in Jakarta or Bangkok go to cafes and do many outrageous things as told by the television characters. They are also spending more money than any youngster ever experienced one or two decades ago. This kind of lifestyle, of values, is accepted in such a way by Indonesian, urban teens or probably by many other teens in other parts of the world. These contemporary values (of new reality) are questioned of leaving real life behind:

“… entertainment world could then become ‘a new leviathan’, ‘an entertaining leviathan’, a leviathan that grabbed the people’s attention with everyday amusement, not knowing that many important things are left behind in real life.”[v]B. THE EVERLASTING DEMAND OF TELEVISION LIFESTYLE

Hollywood is now a concept, not a town. Alteration of Hollywood or even MTV came across the jargon “gue banget” as individualistic values hence a part of capitalism. There is a line of attack in the economy when tastes in teens’ attire are inserted in every programme, or even inserted as information of the latest news of the so-called idols. The creation of an idol in “Singapore Idol”, or programme of “Salam Dangdut[vi]” or “Slam Dut”, is cosmetics. It is an insertion of global lifestyle on behalf of localism. Localisation of MTV programmes is a path of globalisation for the minds.

The concept of idol has changed a lot. There was a time when the idol could be Hitler or any local heroes or heroines. There was a time Madonna and Elvis invaded a family living room or bedroom. Today, the crystallization of idol has been localised. Canadian Idol to Singapore Idol derived from entertainment franchisers’: the Hollywood brains. The idol wears a new jacket of capitalism: from SMS gambling business to the way he/she wears or drinks as often shown purposively on the tube.

Suzy Lake insisted that “… audiences were media-savvy enough to see Canadian Idol’s marketing mission … the Pygmalion factor is irresistible.” She also concluded that “fame is a lifelong dream for many; it’s a mundane manufactured commodity for the industry. In fact, [Lake notes,] the show itself is really a season-long TV focus group playing as entertainment, gauging what audiences want to hear and see in a pop idol, from voice to looks to musical repertoire to hairstyles.”[vii]

The music is just a diminutive product. Total lifestyle becomes the main item for consumption. The message of MTV is an overall economy packet. Condom is a major advertiser in MTV Indonesia. Cafés and night clubs post television sets at the corners showing MTV. Demand for MTV off-air programmes is high; talent search of video disc jockeys (vee-jays or VJs) is always welcome in many cities in Indonesia. This is not a bad thing at some points of fact, but what does it mean? Does this phenomenon have significance toward the culture or media industry in ASEAN countries?

Today, ASEAN youngsters are just a big fat market[viii] for MTV Asia management. This mechanism works: grab their minds then tell them to spend [money] the way I tell them to. This thing works that way, and today we must comprehend this effort positively. Let’s re-phrase the above inquiry like this: “How are we going to make use of ‘MTV edification’ for self benefits or for enhancement of the culture or media industry in ASEAN region?”

C. BROADCASTING IN ASEAN

Contrary to MTV’s proposition, the overview of broadcasting industry in ASEAN region is rather myopic. Domestic situation in each country leads to inconsistent structure of the industry. Myanmar, for example, has only military or government owned-and-operated TV stations. Compared to Brunei with RTB (Radio Television of Brunei, a government owned-and-operated station, Singapore has a more aggressive plan in broadcasting: a law, independent regulatory body, and private stations[ix]. Thailand and Indonesia have similarity in terms of regulation structure[x].

The latter two countries have a complex industry landscape, taking advantage of each unique awkward political situation. Brunei, Laos, and Viet Nam have also similar situation with only solitary concept for the country: government owned-and operated stations. Cambodia, on the other hand, has a well-off situation, allowing private stations to operate. Unfortunately, Cambodia’s regulation pointed specifically on broadcasting sector has not been issued yet.

Table 1: Demographic and regulation mapping of each member country [xi]

| Country | Population (2004) | Area (sqm) | Broadcasting Law | Regulators appointed by law |

| Brunei | 357,800 | 5,765 | 2000 | Government |

| Cambodia | 14,131,000 | 181,035 | (none specific) | Government |

| Indonesia | 215,960,000 | 1,890,000 | 2002 | KPI |

| Lao PDR | 5,758,000 | 236,800 | (none specific) | Government |

| Malaysia | 23,671,000 | 330,257 | 1998 | MCMC |

| Myanmar | 54,745,000 | 676,577 | (none specific) | Government |

| Singapore | 4.198,000 | 697 | 2003 | MDA |

| Thailand | 64,470,000 | 513,254 | 2000 | NBC |

| The Philippines | 82,664,000 | 85,237 | 1963 (radio only) | Government |

| Viet Nam | 82,222,000 | 330,363 | (none specific) | Government |

Table 2: Regulation in each country

| Country | Type of broadcasters | Foreign Ownership | Content | Regulators’ independency |

| Brunei | Government [sole] station: RTB | None | (included in Broadcasting Law 1998) | None |

| Cambodia | Private and public | None | None | None |

| Indonesia | - Public (TVRI or RRI)- Private or commercial- Community low-powered- Subscription TV | 20% (FDI) | - P3SPS (code of practice and code of ethics)- Draft of Subscription TV Code | KPI(Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia)KPI has central office coordinating with 33 provincial offices. KPI only reports to the President and House of Legislative each quarter or semester annually. |

| Lao PDR | Government stations (4 channels) | None | None | None |

| Malaysia | - Public (RTM1 and RTM2)- Private- Subscription TV | (based on MCMC study of a player’s market power) | - Content Code- General Consumer Code of Practice | MCMC(Multimedia and Communication Commission) under the Ministry of Water, Energy, and Communication |

| Myanmar | Government and military owned-and-operated stationsNo private broadcaster allowed | None | None | None |

| Singapore | - Private- Subscription cable operator (satellite dish is not allowed) | None | - Code of Practice- Subscription TV Program Code | MDA(Multimedia Development Authority) under the Ministry of Information, Communication, and The Arts (MITA) |

Table 2: Regulation in each country (continued)

| Country | Type of broadcasters | Foreign Ownership | Content | Regulator independency |

| Thailand | - Private- Military or government owned-and-operated stations- Community radio- Subscription TV | None | None specific | NBC(National Broadcasting Commission) with members from the so-called regime in power |

| The Philippines | - Private, local- Subscription TV (local operators with network business model) | None | Presidential Decree 1986 (created the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board [MTRCB] on 05 October 1985) | - National Telecommunication Commission- Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB)No further info |

| Viet Nam | Government only: VTV (3 channels) and HTVNo private broadcaster allowed | None | None specific | None |

This unfortunate and chaotic situation would go downhill further. To illustrate a complex situation, let’s focus on one country. Indonesia’s Broadcasting Law, issued 4 years ago, has not effectively made any progress up till today. The dominant players centralised in Jakarta insist on abolishing the concept of independent regulator, one way or another. One evident case, broadcasting standards that were issued last year for both content and management[xii] made by KPI was heavily rejected mostly by Jakarta players. Quite the opposite, players of other provinces, mostly fringe firms or new entrants, accepted the regulations straightforwardly.

In the so-called lawlessness (no law is obeyed effectively by dominant players), new TV and radio stations emerged, using other station’s frequency allocation, or interfering the nearest existing station’s allocation. This chaos only happens in 9 most populated provinces (North Sumatera, Riau Islands, West Java, Central Java, East Java, Jakarta, South Sulawesi, Bali, and Banten).

In outer space, Indonesia also faced a catch-22 situation with Astro Nusantara, a joint-cooperation of Malaysia Media Prima’s Astro Malaysia and Indonesia Lippo’s Kabelvision concerning landing rights license for using Measat 2 satellite. At the same time, dialogue on Measat-2’s satellite coordination with Garuda-1’s is on the way. Malaysia’s Astro has invested heavily on the infrastructure and programming for two years, then suddenly its DTH company in Indonesia is banned by Directorate General Post and Telecommunication (an executive body) from operational right after its soft launching. House of Legislatives questioned the bottom of this problem earlier this year.

This uncertainty toward investing in the broadcasting sector has happened in Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines, too, with each distinctive background. Malaysia does not allow other players in DTH operation up till today. Thailand has sky-scraping rate of DTH signal piracy. The Philippines is a free market with many fringe firms.

The chaos like what Indonesia or any member country has gone through is a lesson to learn. In contrast with sharp global industrialist like MTV, industry in ASEAN does have a little notice of “capitalism per se” out of broadcasting signals. Advantages that MTV has gained should not, must not, be taken for granted, if ASEAN wanted to learn and improve. ASEAN chaotic situation surely elevated high transaction cost[xiii]. This resulted to less efficient situation for the local broadcasters’ operation. Further result would be market failure and government failure[xiv] at the same time. At the end of the day, the people had to suffer.

D. BROADCASTING REGULATIONS

A decade ago, the firms in ASEAN region who operated and broadcasted signals had been regulated heavily not because of market failure[xv]. The government was more concerned on “educating” the people in own terms[xvi]. However, regulation toward broadcasting firms has transformed progressively. The Government and/or House of Legislatives of Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Brunei assembled laws and regulation to remedy the failure[xvii]. As a result, broadcasting system is a structural concept of values mixed with market.

The ever-changing, zonal problems or phenomenon (that is market failure) could not be solved unless existing laws or regulations are re-formulated or de-regulated. Government intervention at some points of fact is still needed:

In spite of considerable deregulation in the 1980s, the government has continued to play a significant role in markets that are firmly believed to be natural monopolies. Most economists argue that there is a need for government intervention in some capacity when social optimality requires a single firm to produce some good or service. It is because we foresee a continued role for government intervention … [xviii]

In a country like Indonesia, broadcasting laws and regulations implemented during the first half of its existence aimed at public utilities for more extensive and fairer distribution to the people. On the second half deregulation took place gradually to correct market failure, or in other words, to regulate firms. Centralised broadcasters, the dominant players, were stationed in Jakarta. The first ever Broadcasting Law was issued in 1997 then amended 2002. The new Law was aimed to decentralise firms to other parts of the archipelago.

Toward this centralisation of broadcasters, some economists believe that “monopoly as behaviour” is considered harmful toward public utility. Some other experts also think natural monopoly is just fine[xix].

Also for the reason of “monopoly” for many years, public service broadcasters in many countries, including in Indonesia, had to be re-formulated. The content and funding had to be rationalised. TVRI, for example, was a government’s instrument of propaganda for 30 years. The content was left behind by the time commercial broadcasters were introduced in late 1980s. Even today, after the existence of Broadcasting Act 2002, TVRI’s content has not improved significantly. In some ways, Indonesia must learn from UK’s public service broadcasters, where Ofcom received many public consultation papers regarding UK’s public service broadcasters.

… we are (and were) surprised that OFCOM should [in 2.13 of the Phase 3 report (and earlier)] adopt such a narrow econometric view of the relationship, which does, should and can exist between commercial broadcasters and society … [T]his also ignores the wider cultural and social responsibilities, which inevitably and rightly are the province of and devolve to makers and re-makers of culture and society such as broadcasters.[xx]

When civil society has fully participated in re-organising the PSB, the regulations would be formulated extensively, therefore could be implemented properly. Where the monopoly of PSB is reduced in some ways, for example, it should or must not be harmful toward the PSB’s daily operation nor be harmful to society, PSB could compete healthily with commercial stations.

For commercial broadcasters, market failure happens when they are highly concentrated in one service area. Diversity of content would not be the outcome. The people have no choice. In other words, monopoly that is a creation of PSB is, by some means, different from commercial broadcasters.

The illustration above leads to an important point. As the people are redirected to values broadcast on our screens (that is MTV en route for youngsters), ASEAN member countries have internal problem to solve. The messy broadcasting structure and infrastructure leads also to uncertain future. How to regulate this industry for stability goal at one side, thus for taking advantage of ethereal mechanism for ASEAN benefits?

E. ASEAN AS INSTITUTION AND ASEAN STATUS ON THE SUBJECT OF BROADCASTING REGULATIONS

Evolution is happening toward the ASEAN as institution. ASEAN is evolving from inter-governmental cooperation to legally binding for the people thus the government. The notion of “individual and learning organisation” like ASEAN has become an intense focus today.

What are the implications for modern day policy makers? Institutions matter. But how? The neo-classical economic policy maker would certainly concede that institutions exist but would implicitly or explicitly argue that they are a dependent variable in policy making. In effect all one need do is create the conditions of competitive markets by freeing up prices and exchange rates and competition will do the rest; i.e. create the necessary institutional framework of rules, laws, norms of behavior and enforcement. But fundamental doubts about such a policy prescription are raised by the foregoing analysis. For one thing the institutional evolution of efficient markets was a long evolutionary process in Western Europe. Can it be done overnight? In particular can it replace overnight an institutional matrix with radically contrasting incentives and norms of behavior? Will the new property rights that undergird competitive markets appear automatically? How long does it take to create an enforcement system of courts, judges, and a legal framework that will impartially enforce contracts? Will the appropriate norms that complement contract enforcement appear?[xxi]

Problems and possible solutions have been cultivated and redefined by the school of new institutionalists. ASEAN remodeled its institution with advanced bodies and means thus transformed its objectives. As the former organisation answered little to the complexities of the member countries’ inquiries, the new ASEAN institution gained knowledge of European Community’s successful story: involving civil society for ASEAN policy recommendation. The concept of Eminent Persons Group (EPG) was officially announced on the 11th ASEAN Summit “One Vision, One Identity, One Community”, in Kuala Lumpur, 12 December 2005.

… the so-called Eminent Persons Group of ASEAN consists of 10 persons. One person from each member country of ASEAN. So we are 10. And we are tasked with coming up with ideas, suggestions, proposals and recommendations to the leaders of ASEAN on a possible charter or constitution of ASEAN. We are not supposed to write the charter ourselves. We are going to write a report in which we will present our recommendations, what the content should be according to us. But then the senior officials of ASEAN will probably form a task force and they will actually write the charter on the basis of our proposals, at least those which have been accepted by the leaders. And they are supposed to write down and we are asked to be bold and visionary, as they say, to write down our views on how ASEAN should evolve and how this charter could serve as a legal and institutional framework for the new ASEAN in the future. Because, as you know ASEAN has for many years been a successful association. Meaning, a rather loose organisation, having no constitution or charter but quite successful in its work. But now it is ready to move towards a new phase in its existence, namely a community. And a community requires a firm foundation, a legal personality, but also an institutional framework which is capable of meeting all the demands of the new era in which ASEAN is moving and to which ASEAN is to adapt itself.[xxii]

In the Summit, the Chairman of ASEAN also introduced three pillars for ASEAN Charter 2020: ASEAN Security Community (ASC), ASEAN Socio-cultural Community (ASCC), and ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). AEC pillar was established specifically to meet the demand of this fast changing world in the business and economic realm. EPG was formed also to meet the demand of the people.

For a long time, we in ASEAN have been accused of being a rather comfortable club of the governing elites of ASEAN. (As for) the people’s organisation-we are very much aware of that-having served under Adam Malik, in the early years of ASEAN, Adam Malik actually very much propagated the fact that ASEAN should move towards (being) a people’s organisation. I was his secretary then. And he tried very much at that time, but the time had not come yet. But now however, we have a very active civil society, not only in Indonesia but in many other ASEAN countries. We will certainly listen to their views. We will certainly listen to the views of our parliaments, we will listen to our think tanks. We are going to make cohesion of this in our work. And we will certainly give the opportunity to all these groups, as far as possible, to present their views to us.[xxiii]

Forming EPG as an ad hoc body to give recommendation for the concept of ASEAN Charter 2020-also considering a more legally binding institution-ASEAN learns from mistakes. Mistake number one: ASEAN focus of communication and information sector, concisely broadcasting sub-sector, has always been placed as political or socio-cultural aspect[xxiv], rather than economic approach. The dark side of this matter is that landscape of the cable-satellite-terrestrial broadcasting industry in ASEAN member countries has been overlooked; consequently this multifaceted industry has grown hyper-commercial yet less beneficial to the people.

Mistake number two: Out of the unbearable situation, member countries used less information management to promote their countries. Probably only Singapore and Thailand excelled with tourism promotion via media. Others were even unable to maintain equilibrium of domestic situation[xxv] in some manners.

The chaos, as mentioned before, sprung from the situation that not all countries have laws and regulations regarding broadcasting sub-sector. To add the complication, not all laws impose on the creation of independent regulators[xxvi] for broadcasting. Broadcasting laws and regulations of the Philippines, for example, are enforced by Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) with National Telecommunication Commission (NTC) and Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB). Indonesia also has separate Broadcasting Laws 2002 and Telecommunication Laws 1999, with different institutions to enforce the regulations. Singapore and Malaysia are fortunate to have a converged law; still independent regulators to regulate are not, in actual fact, independent[xxvii] from the so-called regime in power.

By establishing EPG, ASEAN will listen more to the people’s needs. ASEAN must thoroughly scrutinize broadcasting as means for prosperity (of the industry and the people in balance). All this time, ASEAN put broadcasting only as socio-cultural pillar or security pillar; never as economy enhancement factor. To reach prosperity, ASEAN must consider standardisation in the broadcasting sector-just like tourism or air transport sector-as a factor of the region wealth management. To know the standards of broadcasting sector, let’s take a quick tour on the compartmentalization of the industry[xxviii].

F. BROADCASTING AS A SYSTEM

Dual system in the United Kingdom has abolished the conception of public service broadcasting (PSB). Competitions for a better content were encouraged. Ofcom (Office of Communication), the independent regulatory body for broadcasting and communication, are charged by the Communications Act with assessing the effectiveness of the designated public service broadcasters (BBC, Channel 3, Channel 4, Five, S4C and Teletext), taken together, in delivering the public service purposes set out in the Act. The quality of public service broadcasting must be maintained and strengthened in future, in order to establish a clear and settled framework within which the key PSB providers to focus on where they can each add most value.[xxix]

Public broadcasters in ASEAN countries, on the other hand, are at its façade stage. Indonesia has the national-coverage TVRI (Televisi Republik Indonesia) airing side-by-side with approximately a hundred of other commercial stations. However, Brunei has RTB (Radio Television of Brunei) and Myanmar has MRTV (Myanmar Radio Television) as sole and official broadcaster of the country. RTB and MRTV are government owned-and-operated stations. TVRI used to be government-owned, but the Broadcasting Act 2002 instructed that TVRI must re-format its organisation and programmes to meet the public needs.

Indonesia Broadcasting Act 2002 also produced other two concepts of broadcasters beside PSB and commercial broadcasters. The third concept would be community television or radio to be developed in many remote islands of Indonesia. This low-powered, small-budget broadcaster aims only at roughly a hundred listeners of the neighbourhood.

Picture 1: The road to a community radio and its humble studio (Garut, Indonesia, 2006)

Picture 1: The road to a community radio and its humble studio (Garut, Indonesia, 2006)

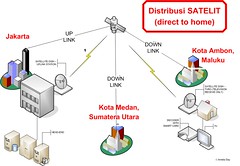

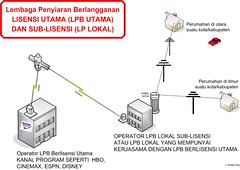

The fourth type of broadcaster, an already popular type in other countries, is paid or subscription broadcaster[xxx] or operator. DTH (direct-to-home via satellite) operator or cable operator provides multi-channel services to subscribers at certain monthly fees.

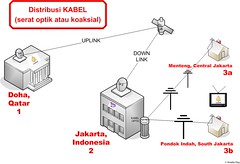

All types of broadcasters (public, commercial, community, and subscription-base broadcasters) are not strict compartmentalization of signal distribution. Local cable operator can be considered community broadcaster since the firm only has 100 subscribers[xxxi] (see below picture).

Picture 2: Local cable operator in Kalimantan, Indonesia, with antenna farm overhead. This local cable is using fiber optics and internet-ready infrastructure. The whole city is inter-connected with the optics without government subsidiary funding, since every home pay a certain amount of money for every 10-meter cable.

Picture 2: Local cable operator in Kalimantan, Indonesia, with antenna farm overhead. This local cable is using fiber optics and internet-ready infrastructure. The whole city is inter-connected with the optics without government subsidiary funding, since every home pay a certain amount of money for every 10-meter cable.

To trick the situation, cable is also using satellite uplink. Free-to-air (FTA) commercial television is using satellite to reach other side of the country. Community radio for networking with other radio must also use satellite.

By any delivery system or business model, each type functions as distinct signal distributor for serving the entire archipelago. The conception must also consider challenges of commercialisation vs. educative programmes, free vs. subscription business model (funding method), and low- vs. high-powered technical operation.

As for the people in an island like resort island of Langkawi, Malaysia, having a multi-channel television set could be established by cable or satellite (DTH). However, if the island has a well-managed fiber-optics infrastructure, quite reverse, placing DTH dish in every hotel or bungalow can be expensive. Moreover, due to the hilly contour of the island, one expensive terrestrial tower in is not enough, not to mention one tower means merely single channel.

Picture 3: DTH operator

Picture 3: DTH operator

Picture 4: Cable operator

Picture 4: Cable operator

Picture 5: Local [franchised] cable operator

Picture 5: Local [franchised] cable operator

For another area in Indonesia, a more populated city, say Jakarta, with no cable infrastructure ever placed efficiently, DTH is a choice. For Jakarta, terrestrial commercial services, or FTA services, could face another problem. The limited frequency allocation and advertising expenditure would be the restriction for their expansion.

For remote, less inhabited islands in Indonesia, low-powered small budget community broadcasters could be the answer. Even in isolated area in Indonesia’s Kalimantan jungle or a village in land-locked, mountainous Phou Bia City, Laos, a hundred villagers could communicate and unwind by listening to community radio, owned and operated by their people.

With many matters arising uniquely in each ASEAN member country, concurrently and conversely, compartmentalization does also mean simplifying the regulation and its enforcement. Compartments of broadcasting industry have been assessed as the ideal blocks in Indonesia, and even in many developing countries. Standardisation, as mentioned in the last paragraph of explanation D above, starts from understanding this compartments (see table below).

Table 3: Type of broadcasters and each type’s assessment

| Type of broadcaster | Means | Coverage | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Public | - Satellite- Terrestrial | Nationwide or local (terrestrial) | Non-commercial expose | Funding controversy |

| Commercial | - Satellite- Cable- Terrestrial | Nationwide (satellite) or local (cable or terrestrial) | Free-to-air (means no direct fees collected from the people) | Commercialism with any possible method |

| Community | - Terrestrial low powered | - Local, limited population- Remote areas | - Non-commercial expose- Reaching remote areas/islands- Low-budget operation | Unknown concept (how to do it for the first time, why not commercial, what is the ‘business model’, etc.) |

| Subscription | - Satellite- Cable- Terrestrial | Nationwide (satellite) or local (cable or terrestrial) | - Multi-channel- Thriving for its funding method | Selected segment (A-B class) |

G. TREADS TO VISION 2020

To meet the commitment of “more integrated economic region”, reaching the 2020 Vision, ASEAN as a re-born institution must include broadcasting sub-sector in a bigger picture. This is because-once again, and never put this notion behind-that broadcasting a signal ought to mean beaming values. Second reason, ASEAN needs to distribute Vision 2020 more effectively, starting today. Using the signal to accelerate the vision internally or externally, there are steps to consider beforehand.

First of all, disarray of broadcasting institution in ASEAN could be seen as colourful picture on a white canvas. When the colours are attacking-even hurting-the eyes, surely we must re-arrange it, and it starts from picking the right palette. Picking the right palette is positioned at the foundation stage.

Next stage is enforcement stage: efficient regulator is formed to enforce the law. This would lead to equilibrium stage of the industry. When it does happen, conducive situation signifies healthy industry. At the same time, the industry would distribute Vision 2020 expansively.

At the first stage, re-arrangement of laws as the foundation, the palette, must calculate provisions of the law. Only “old members” have specific law on the subject of broadcasting. The structure and norms in the specific law made are quite similar: the type of broadcasters, content, ownership, and regulator in charge. Consideration of the structure (and embedded norms along with it) would abridge further regulation.

After studying the socio-cultural-economy dimension of broadcasting[xxxii], we conclude that structure and content go hand in hand; furthermore broadcasting regulation must always consider how the industry structure formulates the content. Most of “old member” laws already include content regulation, yet with different degrees of regulation.

Content-wise, at some degrees, must be regulated heavily. VHS (violence, sex, horror) is a popular, easy-to-remember term in a broadcasting content regulation. Each member country has unique values to consider. Expose of woman’s particular body part in Aceh, Indonesia, would face penalty of physical batter. Next door province, North Sumatera, would take the body exposure calmly. To add the complication, security issues are one thing that ASEAN is focusing today; and with content aired is strictly regulated, any effusive topic can be avoided.

Next to content, there is the industry structure to consider. Structure also suggests ownership concentration and behaviour. Due to persistent monopoly power in many markets, School of Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) insisted that “government should implement a relatively high-level competition policy … European Community has developed in the structure-conduct-performance tradition. In the European Community, the policy goal of maintaining competitive markets has been tempered by another purpose, that of furthering European integration”[xxxiii]. Highlighting the phrase “another purpose that of furthering European integration” that was conducted in Europe, outlining regulations must first put this objective on top of everything.

Regarding approach to use, regulations toward behavioural approach have been implemented by Singapore and Malaysia Broadcasting Laws[xxxiv]. SCP approach, that is more to target percentage of ownership at certain number, would have loopholes. For instance, Astro Nusantara in Indonesia would not be allowed to operate if exceed 20% of foreign ownership. Suspected SPV (special purpose vehicle) was established to stage-manage the 20% foreign structure regulation.

Whatever approach needs to be put into action, SCP or behavioural, commitment of each country to settle matters arising must have priority for solution. Further study must be completed to have comprehensive outlook of the situation.

Next stage: zooming into the picture, the concept of independent regulator, consequently, must be internalised consistently. In democratic settings, the concept of independent media-hence independency of media regulator-has been studied and scrutinized. For the last two decades, civil society has grown from passive majority to active participants. The rise of this postmodern culture tallied up with corporate search for public wisdom (and essentials) has formed a new balance of regulation.

Picture 6: Structure of society (quoted from nsw.gov.au)

Government command-and-control regulation is shrinking. More likely media is self-regulated (content wise), and co-regulator becomes an alternative. New form of governance has gradually replaced traditional regulation that tends to operate on an item-by-item basis only, and not in a process-orientated manner.

Yet, this notion must be treated carefully. Out of domestic political reasons, Myanmar and Laos, for example, has additional consideration to reach this strategic approach further. On the other side, the “old members” already have broadcasting laws, but regulators’ functions and tasks differ at some points. On top of that, sketching a thorough concept of ASEAN Charter 2020 that is legally binding must consider the outline of a broadcasting law from economic perspectives. This way, regulations of the law could mean clauses with “investment-heavy” incentives.

Stages, outlined as above, have undetermined timeline yet definite deadline. This uncertainty must be solved with each member country’s political will. Foundation stage may take as long as 5 years to settle internally before enforcement state takes place. The equilibrium of the industry (or market) would find its way when enforcement is executed efficiently. Again, this execution needs a rigid political will of each country.

Systematically, treads to Vision 2020 would come from internal commitment of each member country. Enlarging the picture, we would see a conception of public service broadcasting is at the earliest. Government-owned and -operated system should be transformed gradually. The overwhelming situation of commercial stations must be monitored profoundly. On the other hand, community FTA and local cable broadcasters must be endorsed with incentives.

Satellite birds[xxxv] that are already highly concentrated above ASEAN’s sky ought to be a priority to regulate. Cross-border footprints must have reciprocity understanding. Satellite companies from outside ASEAN must also respect ASEAN’s unreserved jurisdiction, if they want to enter the big fat market of ASEAN member countries.

A reliable and encircled ASEAN cooperation would consider also cross-border production for creating a solid ASEAN identity. Cross-border problems on land (not above the sky), such as frequency allocation, is another number to solve.

Nevertheless, trilateral (Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia) negotiation has been progressing quite satisfactorily in several roundtable meetings of Joint Commission on Communication. While treads for a better broadcasting environment, to the equilibrium stage, is happening, at the same time an effort to promote ASEAN programmes worldwide could take place. ASEAN Directives, consequently, is a big picture with many dimensions.

H. CONCLUSION

To meet the commitment of “more integrated economic region”, ASEAN as a re-born institution has a long way to accomplish Vision 2020; however, announcing the vision through the globe, ASEAN must include broadcasting as an overall packet of acceleration. This includes placing broadcasting in ASEAN Economic Community’s target list. Learning how broadcasting signals work subtly but have long-lasting impact toward audience, re-arranging the industry structure is the first step to better groundwork. Regulator, be it a co-regulator or executive agency, would work efficiently to lead the equilibrium stage. This established situation would therefore succeed the Vision 2020, set in legally binding ASEAN Charter 2020 for all member countries.

Jakarta, June 15, 2006

[i] Jonathan Bignel, An Introduction to Television Studies, Routledge: London, 2004, page 20-21. [ii] Annette Hill, a professor of Media, and Research Centre Director of School of Media, Arts and Design, University of Westminster has scrutinized reality TV phenomenon, and concluded: “Our understanding of moral values is shaped by the principle of mutual advantage rather than natural duty, and we therefore do not have a universal respect for the rights of others, but rather a respect for rights that are beneficial to ourselves, and the community” (2005: 111). [iii] Trade can be seen as exchange of value. In many cases parties exchange money for goods and services. However, if there is trade between a viewer and the broadcaster of free-to-air television, it does not involve any monetary exchange (by definition viewers do not pay for free-to-air broadcasting, and broadcasters do not pay viewers to consume content). But there does seem to be an exchange whereby on the one hand the broadcaster supplies bundled content to the viewer (which the viewer values), and on the other hand the viewer gives access to himself-that is his attention-to the broadcaster (which the broadcaster values) … there is nevertheless exchange of value, which can properly be termed trade. (Report by Europe Economics for the European Commission, DG Competition, Market Definition in the Media Sector, 2002, page 43-44) [iv] See www.capitalism.org, main page [v] Ignatius Haryanto, I am a Celebrity Therefore I am Important (Aku Selebriti Maka Aku Penting), Yogyakarta: Bentang Publisher, 2006, page 30. [vi] Dangdut is a type of folk music in Indonesia, has the same beat with Indian folk music and dance. It is the most popular music among the middle-low class society for the last five decades. [vii] An interview by Murray Tong to Suzy Lake a professor of fine Arts from University of Guelph, Canada, and posted on publication: Whatcha want is a Canadian Idol; The Reality Behind Reality TV, Focus on Society and Culture, Volume XX Number 1 Summer 2005, page 36 [viii] Defining “market” in broadcasting sub-sector is a bit tricky. Teenager is a segment of age; how teens spending daily are another calculation. However, a decade ago, TV management in Indonesia considered teenagers were considered penniless. They were not the decision maker in the house. Today, many ads using teen talents, thus prime time programmes aim at teen market. [ix] Even though private players in Singapore is owned by the one and only Mediacorp, other players from overseas are allowed to operate in Singapore via cable or satellite, not terrestrial coverage, probably considering limited space of the island. [x] However, Thailand NBC’s independency was criticized profoundly due to suspected cronyism of the selected members. In Indonesia, KPI (established in 2002), has been challenged intensely by new branch of executive: Ministry of Communication and Informatics (est. 2005). [xi] All demography data is taken from official site of ASEAN (www.aseansec.org) by March 2006. [xii] Standards in the management were set in the scoring system of the licensing process. Aspects considered in the scoring system is around the company legal format, programming, technical issue, financial and human resources management, and 10-year plan to accomplish the vision. Standards for content-of ethics and conduct codes-considered impartiality, “watershed” time schedule, and trivial issues like SMS and gambling. Programmes showing bloody or sensual scenes are often found today in TV screens (of Jakarta players). Even worse, owners of the stations sometime show up to campaign “as the victim of issues”. Regarding content standards, industry from Jakarta took it to Supreme Court for judicial review. Up till today, the result still awaits. [xiii] Douglass C. North insisted that “The incomplete information and limited mental capacity by which to process information determines the cost of transacting which underlies the formation of institutions. At issue is not only the rationality postulate but the specific characteristics of transacting that prevent the actors from achieving the joint maximisation result of the zero transaction cost model. The costs of transacting arise because information is costly and asymmetrically held by the parties to exchange. The costs of measuring the multiple valuable dimensions of the goods or services exchanged or of the performance of agents, and the costs of enforcing agreements determine transaction costs.” (The New Institutional Economics and Development, 1993: 2) [xiv] The complexity of lawlessness could mean government failure, and unfair information distribution would be market failure. Both will burden the people, regarding bad content (for audience) or ruthless entry barriers (for new players). [xv] When a market failure occurs-whether due to natural monopoly or externalities, or some other source-there is a potential rationale for government intervention … when there is a market failure, in theory regulation may be able to raise social welfare. (W. Kip Viscusi, John M. Vernon, Joseph R. Harrington Jr, Economics of Regulation and Antitrust, London: MIT Press, 1995, page 325) [xvi] TVRI or Televisi Republik Indonesia, that was once government-owned, must transform its vision more to a more public-oriented operation, rather than to government-oriented. The process could take some time to fully comprehend, but at least the process started when the Indonesia’s Broadcasting Act 2002 was formally issued. The concept of government-owned is no longer in place, yet today the public oriented content is far from perfect. Many programmes, like music performance, are produced based on rating by Nielsen Media Research, or at least has the same format with high rating programmes in commercial stations. [xvii] Broadcasting Acts or Laws in these countries has been formally issued during the last decade to anticipate market failure. Take for example, Multimedia Development Authority of Singapore Act 2002 issued Code of Practice for Market Conduct in the Provision of Mass Media Services, or Malaysia Communication and Multimedia Commission of Malaysia Act 1998 issued Guideline on Dominant Position in A Communication Market. [xviii] Supra, 11, page 413 [xix] Benjamin M. Compaine questioned the proposed rules of the Federal Communications Commission for lessening broadcast station ownership limits a reasonable response to court rulings and the changing media landscape or a threat to diversity of viewpoints and to democracy in the United States. He concluded that “The big getting bigger is not the policy objective. Nor is the small getting bigger. Nor is it about a free for all-antitrust law is and will continue to be applicable. But much political capital and human energy that could be better applied to far more immediate and substantial problems are being expended on what is essentially a media system that is robust, competitive, affordable, and provides access to a vast range of entertainment, culture, news and viewpoints. It requires monitoring, and a constraining effect to permit and promote new outlets, not invectives..”(The Media Monopoly Myth: How New Competition Is Expanding Our Sources of Information and Entertainment, 2005, Page 52). [xx] See “A Response to the Consultation”, question by Voice of the Listener & Viewer (VLV), 19 April 2005, page 2. Ofcom received this public consultation paper regarding PSB deregulation to meet the public needs and to compete with commercial broadcasters vigorously. [xxi] Douglass C. North, The Evolution of Efficient Markets in History, 1993, page 6. [xxii] Interview with Ali Alatas, appointed eminent person from Indonesia. This interview was reported by Yuli Ismartono and posted on website http://www.the-leaders.org/library/05.html. [xxiii] Ibid. [xxiv] RTM (Malaysia) and TVRI (Indonesia) once had exchanging (live) programme in 1989. [xxv] Furthermore, out of 17,000 islands spread across Indonesia, 12,000 islands are inhabited. Concentration of population in Java Island includes concentration of TV or radio stations thus advertising expenditures on broadcasting. [xxvi] The latest situation for media regulation in the European countries has been examined (2005) by Hans-Bredow-Institute for media research at the University of Hamburg, Germany, stating that [in media] “… the command-and-control regulation was shrinking, self-regulation was expanding, and co-regulation was soul-searching. All in service of civil society.” [xxvii] Why must this regulator be independent? In short, independency of the media who controls the policy makers must not root from the regime itself. The same thing goes to independency of the regulators, toward the media (the regulated object) and the government (the watched object by media). Co-regulator concept has been fully implemented in European countries and USA. This kind of independency has rooted since government failure was studied and found to cause asymmetric information. Asymmetric information was the main barrier for creating an efficient institution. As a result, this inefficient situation was harmful toward welfare of the people. [xxviii] See Table 2, Regulation in Each Country. [xxix] Ofcom review of public service television broadcasting, Phase 3 - Competition for Quality, Report of Year 2005. [xxx] In many countries, the term “broadcaster” would be considered only with free-to-air (FTA) operation. Instead, the signal distribution via cable or satellite with subscription business model is coined as “operator”. This operator does not produce the content, more like they “compile” many channels and put them in packages (basic or premium) that the subscribers (or audience who pays some amount of fees) could pick. [xxxi] See Picture 2: Local Cable Operator in Kalimantan, Indonesia. [xxxii] This socio-cultural thus economy aspects of broadcasting are represented by MTV as discussed earlier. [xxxiii] Stephen Martin, Industrial Econommics, Economic Analysis and Public Policy, Second Edition, Lehigh Press, 1994, page 2. [xxxiv] Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission has issued Guideline on Dominant Position in A Communications Market (1999), and Singapore’s Multimedia Development Authority has issued Code of Practice for Market Conduct in the Provision of Mass Media Services (2003). [xxxv] Footprints across ASEAN come from many satellite from different frequency slots (geo stationary orbit used for telephony, to KU-band orbit mostly used for military purpose). Above Indonesia’s sky there are about 14 satellite birds in operation.

No comments:

Post a Comment